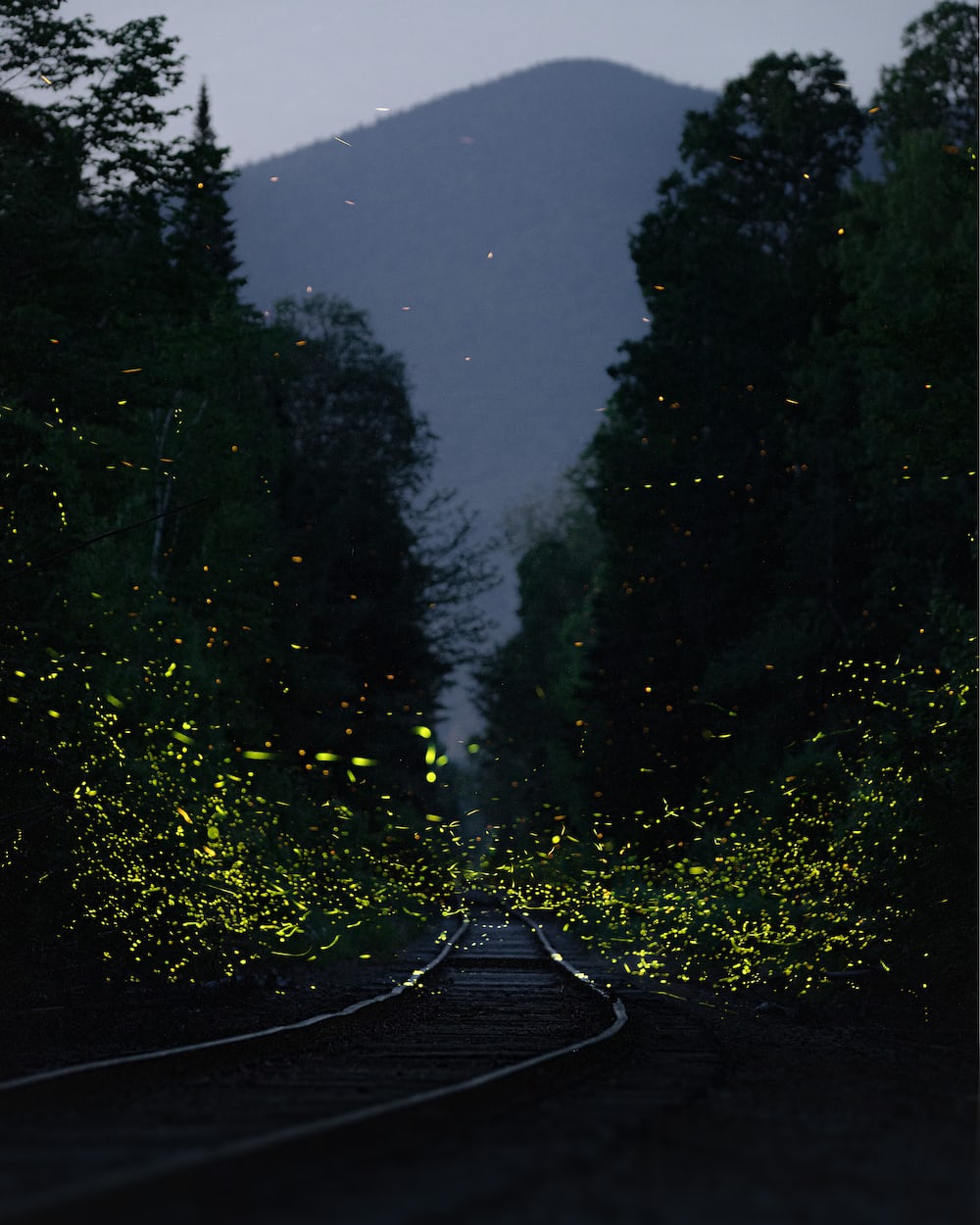

The beginning of the brief spring in the Indian peninsula was generally heralded by a warming of the air and the dance of the fireflies. In recent times, the tourism industry had capitalized on it, and come the end of March, my hometown, a small hill-station in the western Ghats, was awash with city dwellers tired of peering through the dust, and the smog, and squinting against the garish lights which were guaranteed to turn night into day. They drove up from the tech hub in droves, eyes fixed thankfully on the dimness and the rolling hills, more brown than green with the approaching summer.

For them, the darkness was forgiving, hiding flaws, fallacies, and facades instead of highlighting them, so unlike the city lights, which sought them out for the world to jeer at. The darkness worked its own magic. It allowed itself to be rent apart by the fireflies’ dance, a glowing web of moving pinpricks of light cutting effortlessly through its all- encompassing self. Yes, even darkness served a higher purpose in these hills.

It seemed funny, but the fireflies were largely nondescript beetles by day, preferring to hide out in trees and bushes. If it were not for the darkness, they would have led their unassuming existence, busily going about their business, seldom seen, and almost never heard. It did not matter to them if they were called drab by daylight. Their cousins, the butterflies, and dragon flies got all the attention when the sun was high in the sky. But not one of the most garish butterflies could compete when it was time to fight the darkness.

Devaki’s house at the edge of the town, was the best place to watch this night-time miracle because it was built on a knoll which gave way to a steep slope at the end of her humungous garden which spanned nearly three acres. Of course, a large part of it was an orchard, but having explored it for the past twelve years, I could safely say that I knew it better than the back of my hand. I knew where the gnarled roots of the old chickoo tree stuck out of the ground like an angry fist, I knew where the branch of the mango tree almost touched the ground and made a wonderful ‘saddle tree’ for Devaki and me to perch on, and I knew the hollow which turned into a muddy swamp in the rain, where frogs croaked and where the fly-catchers came to feast on the fruit flies.

Devaki and I had been ‘best friends’ ever since she had moved to the hills and joined my class when we were both five-year-old kindergarteners. Since I was the gregarious outgoing one who loved making new friends, I had been the first to offer to share my tiffin box with the newcomer who had stood shyly at the door of the class, clutching her mother’s hand, and staring around with huge, solemn eyes. Her father had recently bought ‘Hill View,’ the only other bungalow in our part of the town. We were neighbors in the broadest sense, separated by only a couple of acres of fruit trees.

Both our families boasted coffee plantations in the surrounding hamlets, though our acreage far outstripped theirs. Her father, having gathered enough through his high- flying finance-job to finance his dreams of leading the genteel life of a ‘country squire’ had left behind the bustle of the city for the quieter climes of the Western Ghats. And thus, the Mary Immaculate Convent had gained a new student, and I had a new friend.

I loved Hill View because it was old in the truest sense. Funny alcoves, dimly lit passages, sprawling rooms, diamond paned windows, and fireplaces, left over as reminders of British times. There were ‘servant quarters’ at the back and numerous sheds, a tennis court, and even a paddock which was forlorn and empty because the horses were long gone. Now, the carriage house housed the smart XUV which Karan Uncle, Devaki’s father, drove. In a smaller shed, her mother’s little Alto crouched like a mongrel puppy which knew that it was something of an imposter in a litter of pedigrees.

Karan Uncle and Nandita Auntie, Devaki’s parents were quite the odd couple. As I grew into my teens, this attraction of seemingly opposites seemed stranger and stranger to my eyes. Not that I could ever mention it to Devaki, but I gave tongue on the subject whenever I could be sure of finding an appreciative audience, which often happened to be my parents, who were among the oldest residents, and whose families had long ruled the echelons of social movers and shakers in the district. It was a close-knit clique which vetted you more thoroughly than prospective candidates for R&AW were. You were admitted into the choicest clubs, soirees, and socials only if you passed with flying colors on all fronts.

And the fronts were many. Blood lines and letters of introduction were the first hurdle at which many fell, but appearance, clothes, shoes, bags, and small-talk all counted. The final deciding factor was of course the depths of your pockets. It was a wonderful mix of the snobbery of the old American South and the superciliousness of the British Royal Court, indigenized in a way only Indians could.

Karan Uncle was the consummate sophisticate. A mixture of charm and rakishness. His handsome face and sharp dressing sense coupled with knowledge on diverse subjects, which made him a sought- after conversationalist, had the ladies swooning at his feet and the men hanging on to his words. He also had a slightly disdainful sense of sarcasm, which made everyone want to impress him. It helped that he had a reputation of having an excellent, almost sixth sense of the investment market. Everything he touched turned to gold and even the Rais, who were counted amongst the wealthiest in South Asia were often seen at Hill View to ‘consult’ him on matters of high finance. It was rumored that he was a close friend of the Finance Secretary to the Indian Government and had turned down an appointment as Special Advisor. His stock in society was certainly as high as it could get for a new comer, which in this corner of the world meant that you had lived here for a mere ten years, instead of ten generations.

Being married to this picture of perfection was certainly a daunting task. Nandita Auntie would have had her task cut out for her, even if she had been Femina Miss India Universe, which she certainly was not. Short, dark, and what kind people described as ‘pleasantly plump and matronly’ and unkind ones as ‘dumpy,’ she was the type of person who could easily melt into the crowd of hangers- on, who trailed the glittering movers and shakers like crows might an eagle. She could have certainly used a good stylist who could give her hints on how to make the most of the few assets she had: long dark hair, smooth skin, and large eyes. But she seemed as indifferent to the kindly busybodies who tried very hard to drop unsubtle hints on how a visit to Jayati’s Salon on Abbey Road or a session with Anjali Devalkar, the ‘go-to’ personal trainer and groomer, might make a vast difference in the picture she presented to the world, as the tuskers to the squawking birds which insisted on following them around, to peck at mites on their skin.

A better dressing sense in soft flowing dresses, well draped sarees or chic trousers and wrap tops, being a better talker, keeping up with the latest gossip, being a part of the various ‘kitty groups,’ or social committees would have certainly helped her to be an accepted member of the inner circle, but she remained stubbornly unheeding. Karan Uncle may have succeeded in raising the stocks of various businesses around the country, but his wife remained his only and obstinate failure. After repeatedly trying and failing to get her to pay the necessary obeisance to the queen bees of society, it was a unanimous decision to ostracize her as far as possible. Vicious rumor mills were rife as to how she was a calculative gold digger, who had somehow trapped Karan Uncle into a marriage which was barely legitimate in the eyes of all the other society matrons.

Nandita Auntie was not fazed in the least. I had never seen her irate or hassled when managing the workers of the large estate while Karan Uncle was away on ‘business’ which was at least a couple of weeks every month. She attended all the social ‘do’s she was required to and seemed perfectly happy by herself, nursing a glass of juice, listening intently to any conversation she might be included in or sitting upright in dignified silence if she was not.

She was polite to a fault, and I had neither seen her cutting someone dead nor gushing over anyone else. She seemed to hearken to a different tune and marched to the beat of a different drummer, whom only she could hear. The rampant gossip and the few and far between invitations more out of obligation, were no secret to her. She knew that she was not the brightest star of the social firmament, but seemed not to care. The unperturbed acceptance of her lowly position on the social ladder was what stuck in everyone else’s craw. Many insiders and regulars in my mother’s circle would have loved to see her grovel her way in. But they had had no luck yet. She was stoicism personified.

Nandita Auntie had a secret lair in Hill View. The old glass house in one of the wings had been converted into a ‘work room’ of sorts for her and was generally kept locked. The window panes on the outside had also been covered by dark film, so that very little was visible. Ever imprudent, I often opined that she ran a secret witch’s coven from there. There was mysterious shelving, petri dishes, several microscopes, and bags of fertilizer in there, according to Devaki who was easily the best botanist in our school and walked away with the gardening prize every year. Why, I often wondered if she inherited her green fingers from her mother as she claimed, was the garden of Hill View a wild tangle of creepers, flowers, spice plants, and undergrowth? Why was the lawn straggly? Why was the garden furniture badly in need of a lick of paint? What about the overgrown lily pond? Most of the busybodies thought that she grew various dangerous plants in there, Henbane, hemlock, deadly nightshade, and the like. It was no surprise that the garden of Hill View was the only one left out of the summer fete list. Another incident which did not graze Nandita Auntie’s tranquility in the least.

The years rolled past with no light being shed on the mysterious attitude of the chatelaine of Hill View. Devaki and I grew up and parted ways when we left for college.

****************************

It was very hot summer when I was in the final year of my management course. I was very happy to be finishing because I could return home and take over the plantation. Coffee, especially the single source kind was the new rage and my parents and I looking forward to being the stars of the coffee export business. A megadeal was in the pipeline. Dad had a new Jaguar, Mom a specially commissioned neckpiece from Garrad’s, and an attitude to match. When the first clouds of the monsoons arrived, they were expected to shower a rain of prosperity.

But the gray clouds were here to stay and it was soon apparent that they had not arrived as much to give, as to snatch away. For the incessant drip, drip, drip of the rains trickled on into late September, the first cause of mild concern. When it continued into October, the tide turned. But when November drew in, the lights of Diwali were extinguished on by one. The beginnings of black rot, a stubborn disease of the coffee plants made inroads into a couple of plantations situated further downhill. The whole district sensed impending doom.

Social soirees, which were the hall mark of Diwali suddenly took on funereal tinges. While the cream of society had diversified business interests which would weather a small storm, black rot was known for its persistence which could mean a considerable dent in family fortunes. Besides, coffee was the foundation of their wealth for most of the old families. Any harm to the plantations was not just inauspicious, but akin to a curse to any wealth garnering activities beyond.

I arrived home to find it enveloped in gloom. Mom was half-heartedly supervising the decorations, while Dad had retired to his office with the estate manager, in frantic consultations with his accountants. Disgruntled plantation workers squatted on the lawn, deep creases furrowing their foreheads in response to the warnings by local politicians that they would be let go soon, with a pittance. Diwali bonuses were a distant dream. This scene was a recurring one in all the ‘old money’ estates. Black Rot had set in in minds and hearts, not just the coffee plants.

Amidst all this, a sudden and surprising invitation arrived from Hill View. Bile rose to the throat of every society matron. How could Nandita think of hosting a meeting? That she was a boor and a bore, was well known. But this was downright obnoxious. Was this her revenge for years of social spurning? Or was she rubbing their noses in the fact that her plantation was doing well? So, they decided to whet their knives and make sure she paid for her crassness. Oh, they would not refuse her invitation, but after they were finished with her, she would be forced to leave for the city, unable to call the hill town home any longer.

When a reluctant crowd, dripping venom, gathered at Hill View, there was a frisson of surprise to see a few political big wigs in attendance. For once, the doors to Nandita Auntie’s lair were wide open and a few coffee plants occupied pride of place on some shelving. With everyone seated and a wave of grumbling threatening to build into a tsunami of anger, the local MLA heaved himself to his feet to introduce the head of the agricultural research office of the state. That gentleman was nearly booed off the make- shift raised platform, until he announced the development of a novel fungicide which had been perfected recently, after which he was almost hoisted on the shoulders of the stiff necks for a triumphant victory march.

Nandita Auntie’s meeting was the silver lining to the cloud of gloom and the knives which had been whetted and the brick bats which had been lined up were quietly put away. She was allowed to continue as before. A few reluctant smiles now came her way instead of the superciliously raised eyebrows and kind, cutting remarks.

One March, few years later, when the district had made its mark on the coffee map of the world a special reception at the District Collector’s Office confirmed that Dr Nandita Rao had been awarded the Life Time Achievement Award by the Indian Botanical Society for numerous contributions, the chief one being pathbreaking research in the fungus which caused Black Rot, which had almost destroyed plantations all over the Western Ghats.

It had taken the nondescript firefly years of dancing to its own tune to allow its glow to cut through the darkness of blindfolded minds…

One reply on “The Dance Of The Firefly”

So so beautifully descriptive. The narrative is gripping like a suspense story. Hats off to Nandita Auntie and the observant writer. Very nice Sumedha.