Diwali was late in arriving the year I was to appear for my class twelve exams. Half of November had already gone by. The first nip of the approaching winter was evident only in the pre-dawn chill. The rest of the day was a mix of a weak but determined sun, drying leaves dropping from the branches and crackling underfoot, and a dry dustiness in the air which clouded the vision and clogged the nose, throat, and lungs. It heralded difficult times.

As far as I could remember, Muniya had always set up her little stall at the furthest end of the chowk, where the market petered out, giving way initially to the one-story tenements which huddled together like ducks at the water’s edge, and later to the towering multi-storied ‘Kothis,’ each wearing the cloak of its grandeur with such grace and dignity that ordinary folk hurrying by averted their eyes out of sheer respect. There was a method to Muniya’s madness. She thought that since the spot was the first on the road from the ‘Kothi end,’ everyone would stop by the stall, for her to make the briskest sales. Alas, the Seths of the Kothis had got where they were by a canny business sense. And no one worth their Innova, Corolla or Verna would even dream of buying anything, even as tiny as a mud Diya without wandering the whole market at least twice and bargaining to the hilt. As a result, Muniya only got those customers who had forgotten something and wanted a last- minute bargain. Of course, the Domino’s outlet opposite Muniya’s stall was blissfully unaware of its exalted status of being exempt from the bargain bustle as people straggled in and out thrusting wodges of cash, new shiny credit cards, or brandishing all kinds of UPI apps on their latest I-phones.

I knew Muniya, because the spot where she set up shop happened to be almost at the very gates of my school, which in keeping with the straggling growth of our town, had added ‘junior college’ to its title. What had started as Mrs. Swamy’s kindergarten and primary school was now the pompously named ‘Dnyansagar High School and Junior College,’ with students, buildings, and fees to match. It was the ‘go-to’ institute in our town for anyone who wanted an admission for ‘higher studies.’ I had called the place alma mater for the past thirteen years and was looking forward to escaping its’ increasingly stifling confines for good in June. Life here was too quiet for me.

Our town boasted ‘colleges’ as well, but they were mostly populated by those who were to follow in their forefathers’ illustrious but not-so-adventurous foot-steps. They were the ones who would inherit businesses, a couple of tile or perfume factories, seats in the state legislature, hectares upon hectares of scrubby farmland, and the like. The girls would inherit jewelry, household chores, and husbands and in-laws, who might or might not treat them right. Everything about the colleges in town was a gamble and I knew I was not cut out for the casinos. Of course, fate could always have the last laugh by bringing me back as a minion to someone who had gone to college here, but I at least had a fighting chance to make a clean break for good. And I determined to grab it with both hands. Besides, as the offspring of a demonstrator in the local science college, I knew I would not inherit the laboratory.

As far as inheritance went, it was a spirited tug-of-war at home. Maa ruled the household with an iron fist and the thought of my moving to a far-away city was still a major bone of contention for her. She wanted me to inherit Papa’s meekness and listen to her. He wanted me to inherit her obstinacy and move far away. So far, Maa’s traits and Papa’s wishes were winning hands down. Maa’s temper flared far more frequently than usual as the dates to fill out forms for the entrance exams neared. She made her displeasure known by nit-picking over the most minor expenses incurred by Papa and me. My last purchase of a new pen had been greeted with “Dadaji ne Khazana jo rakkha hai. Aur udao paise.” Pocket money was a fond distant memory and my occasional expense was being met by the grubby fifty, tenner or twenty surreptitiously slipped into my hand at great personal risk by Papa.

Preparations were doubly frenzied as November pulled on in its mechanical, melancholy way. While Maa busied herself with the cleaning, cooking and candle-stick making, Papa harangued me every day about when the CUET forms would be out and when was the best time to fill them. If I was to travel out of town to the best the Indian Universities had to offer, I first had to clear the CUET (Common University Entrance Test), a relatively new player in an arena dominated by such stalwarts like the JEE, NEET, BITS, and other heavy weights too onerous to pronounce. When the dates were finally announced, I thought Papa would burst a blood vessel due to all the excitement, and fervently hoped that the vermilion used for the Lakshmi Puja would be the usual Alta from Maa’s cupboard, not tainted by a few drops of Vishnu Sharma aka Papa’s blood.

But Ramji, Mata Lakshmi, Thakurji, and Dhanvantari had all had an ear out for us and heard our collectively fervent prayers. While the internet and the server and all the other paraphernalia required for the smooth filling of an online form did turn snooty and try to play spoilsport, they were finally coaxed into best behavior by much cursing, muttering, and finally earnest entreaties on Papa’s part. I could have sworn that the Diwali decorations swayed a little in the gust of the breeze caused by our collective sigh of relief. At least one hurdle had been crossed. While the exam itself loomed ahead, there was a jubilation in the air. My participation at least had been confirmed. Perhaps this was how the Indian contingent felt enroute to any major sports event, slightly bemused by the drama of it all.

Since I was feeling rather pleased with myself, I decided that I needed some time off. Maa however, had been lurking by the door, awaiting just such an opportunity. My plans of heading off to the ice-cream parlor at the corner to literally ‘chill’ with a couple of buddies were rudely disrupted when the rough coir bag was thrust abruptly into my hands, together with a crisp hundred rupee note and admonitions to fetch a dozen mud diyas, along with wicks, some oil, and a garland of marigold flowers for the pooja the next day. “Remember to bargain well. Go to three or four stalls at least,” Maa was still shouting instructions as I ambled off, desperate to get out of ear-shot.

Teenage rebellion always rears its head unexpectedly and I decided to rebel by deciding NOT to bargain. I would buy the supplies at the first stall I came across. Maa would seethe gently, but there was not much she could do about it. Smirking at the thought, I halted at the first stall which of course was Muniya’s. With her mud-brown lehenga and choli, she blended in perfectly with the background, as she sat surrounded by diyas of many types. There were the simple ones, cowering in their basket as if ashamed of their lowly status amongst the more embellished ones, with a floral twirl here, a leaf there, all adorned with gilt or garish colors. There were multi-tiered ones, some shaped like peacocks and others like swans. There were ‘jodis’ or pairs of elephants with upraised trunks. Light, in our town shone in myriad ways.

Normally, the sight of a potential customer sent Muniya into transports of delight and everyone who paused at the entrance to the makeshift tent which was not just her stall but also her home for the few days of Diwali was treated to her hopeful smile and cheerful sales banter. But something was amiss today. She sat sadly amidst all the lights, the spark from her eyes replaced by a dull hopelessness. Kallu, her son slumped next to her, his books lying forgotten, fingers feverishly jabbing at the buttons of the ancient mobile phone in his hand.

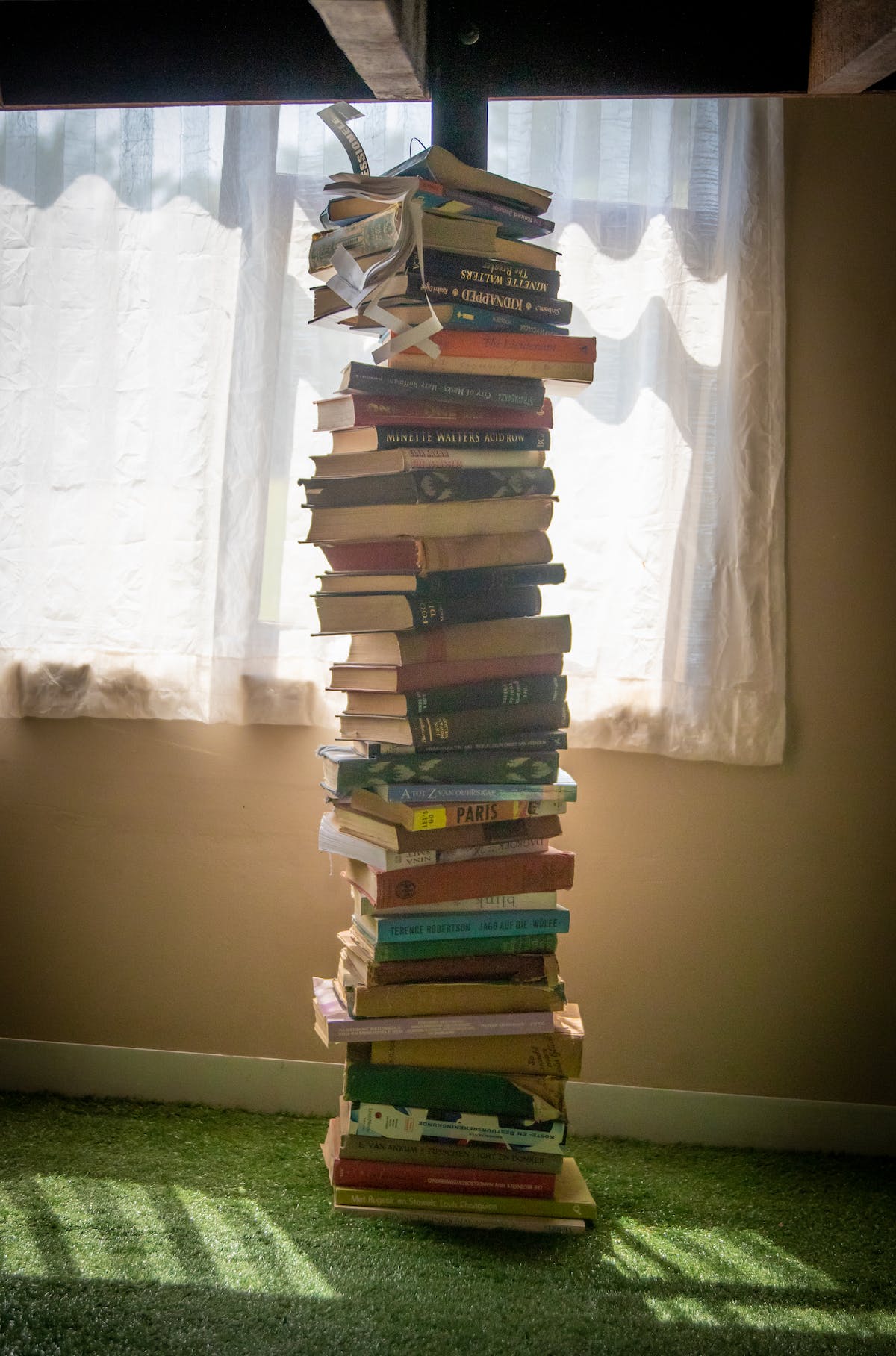

He was a hard-working boy, Kallu. During Diwali, he helped his mother at the stall. The rest of the year, the mother-son duo sold roti and aloo-sabji at the railway station, Muniya setting up her chulha at the crack of dawn, to be joined by her son when he finished school in the afternoon. This continued till the last passenger train left at ten in the night, with Kallu often spotted sitting under the meagre flickering light of the station clock, rapt in his books. He had managed distinction in his class ten exams and it was plain that Muniya had high hopes for him. On the first of every month, Kallu meticulously paid his fees at the office of Bhaskar Vidyalay, a government sponsored initiative for subsidized education of the underprivileged.

Perhaps it was the enquiring look in my eyes, or perhaps the fact that I was the same age as Kallu, but before I could so much as pick up a diya, Muniya was standing before me, hands joined in supplication. “Kallu ka faaaram bharna hai, Babu,” she began. So, this was what it was all about. With the typical oblivion of the better placed, I had never imagined that Kallu had any educational aspirations beyond class twelve. Perhaps the snobbish part of my mind did not think him capable. But Muniya’s litany of woe told a different story. Thanks to a new scholarship scheme, Kallu stood a chance of getting into a polytechnic college. But he had been felled at the first hurdle. Today was the last day for online submission of the application forms, which had been available for a pitiful period of just a week. With his school closed for the Diwali vacations and everyone busy with the festivities, none of his teachers, or the big noises in the tehsil office, or even the station master had answered his increasingly frantic appeals for help. Desperation had made Muniya turn to each one of her customers, but they were too busy trying to light up their own lives, only stopping to bargain for a diya or two. The diya seller was fated to a dark Diwali.

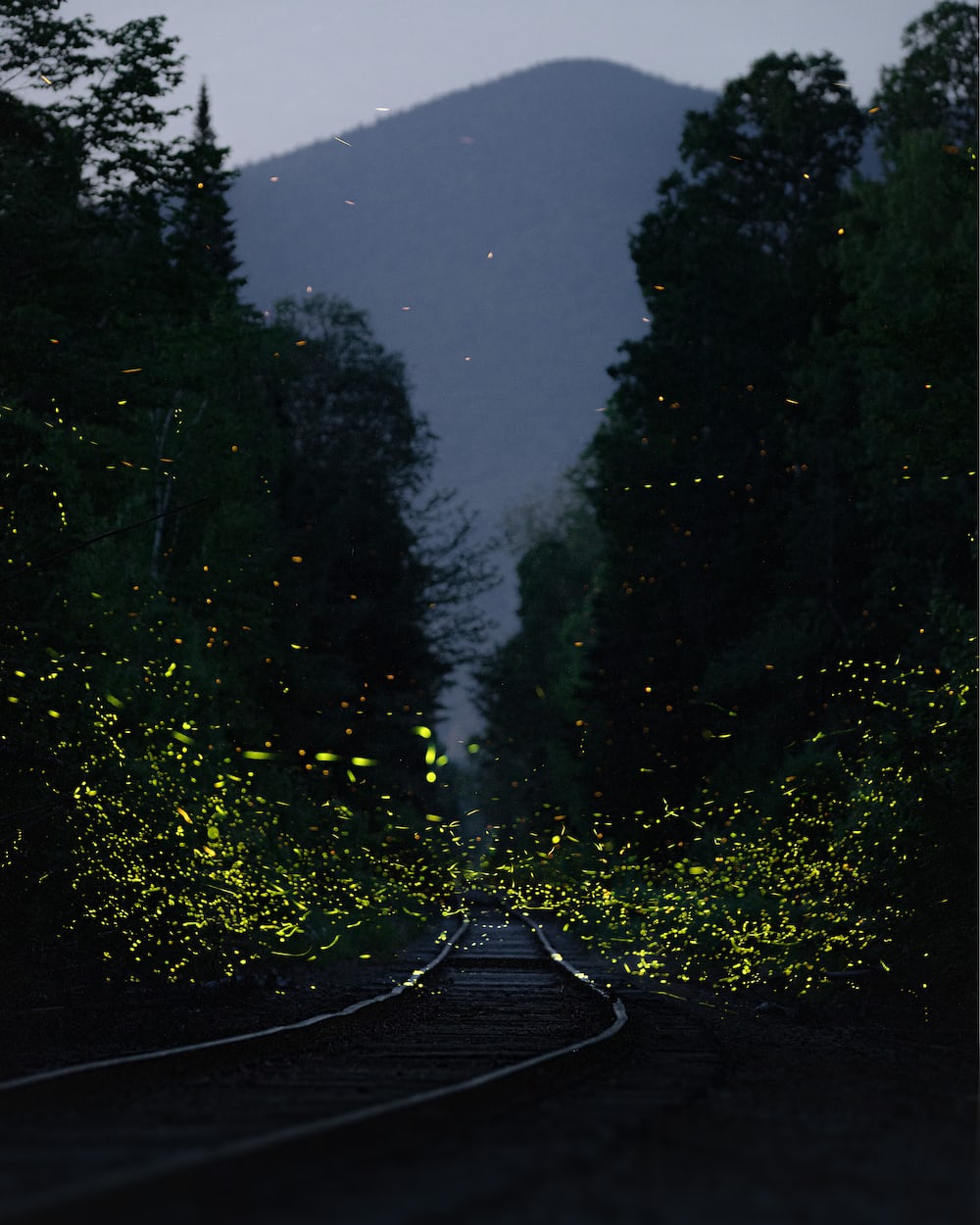

When I made my way back home, it was past sun set. Oil-and-wick mud diyas were winking to life on verandahs and thresholds. A gentle glow permeated the narrow lane as I ducked into the courtyard of my home, only to confront Maa standing there, arms akimbo. Only the Sawari of the roaring tiger was missing in her tableau of the vengeful Goddess. Papa, as usual stood meekly in her shadow. Clearly too furious to speak, she merely thrust out her hand for the pooja paraphernalia she had ordered me to fetch.

As I quailingly placed a photocopy of the receipt of the cyber-café from where Kallu and I had finally succeeded in filling his form, beating the deadline by mere hours, I felt myself basking in the light of Maa’s radiant smile and glistening eyes. “Tumhara jeevan ujale se bhara rahe, beta,” she said as I bent to touch her feet and seek blessings on Diwali day, “Tamaso ma, jyotir gamayah! (lead me from darkness, towards the light).”