The town had changed beyond recognition in the past decade. The snaking lanes which had always been crowded now simply heaved with jostling bodies, ready to burst their seams. A piquant bouquet of smells were the garnishing flourishes: sweat, dung, rotting vegetables and sizzling oil, the final resting point of batter -soaked vegetables, before they emerged in their new avatar- the largely beloved pakoda. A fitting testimony to a town which took in raw recruits and regularly churned out toppers of the toughest entrance exams in the country.

Nandan stared around him in disbelief, taking in garish new ‘cement’ buildings with glaringly bright glass facades, bigger than ever hoardings advertising the latest successes in the NEET and JEE exams, and the ocean of two-wheelers stretching up to the horizon before melding with it, thanking all the Gods he meticulously prayed to each morning, for giving him the good sense to hire a large, deliciously air-conditioned SUV for the drive from Udaipur. He heaved a sigh of relief before sinking back into the plushness. Gone were the days when he had travelled this route in a Rajasthan Roadways behemoth, specially designed to rattle every bone in the body until it came loose from its moorings. Closing his eyes, he wondered as he often did about the strange twists and turns life took. Never apparent while they happened, they were only visible, after you forced yourself out of their vise-grip. Like the hair-pin bends of a treacherous mountain-road seen only on reaching the summit.

Like the several before him and the several who would come after, he had been too tired to realize the gradual melting away of the dread which had hung over him like a miasma while he lived here as a student in his late teens, pursuing the nebulous dream of admission in a prestigious engineering college. The daily grind of classes, tests, and grueling self-study sessions, laced with dry, dusty summers, lukewarm water, glacially rotating ceiling fans, perpetually chapped lips and parched throats made surviving each day a challenge. The day the results were announced, he did not remember any feeling of jubilation, only one of relief, that he was moving away, away from this town which was a seeker of routine blood-sacrifice as the payment of a fulfilled dream.

He had followed the classic Indian engineering dream to a T. An admission into an established NIT, a four-year course in computer science, an internship in the final year which shot him like a stone from well-oiled catapult into a good US university for his master’s degree, followed by recruitment into Microsoft. He had found the elusive ladder in the snakes and ladders of life. The only point where he had veered slightly off course and rocked the boat was when he married Akira, instead of an Aarti or Ayushi as his family would have preferred. Akira was a fellow Japanese post -grad student. But all was forgotten and forgiven, even by his grand-parents who were otherwise mired in tradition. He was the ‘laadla Raja-beta’ who had brought laurels to the family name. Yes, dreams and pieces of sky were different and disjointed in this disparate world.

He never wanted to return. Perhaps he had been more traumatized while he lived here in his teens than he realized. He still woke up sweat soaked and choking from a recurrent nightmare of being smothered under the weight of stacks of test papers which seemed to drag him to the bottom of an endless pit, the harder he tried to drag himself out. He had also developed a habit of squirreling away a part of any good food, instead of eating it all, which had first surprised and later irritated Akira. “You can eat anything you like Nandan,” she had tried reasoning with him, until finally giving up in sullen silence. Luckily, she had put it down as an ‘adorable quirk.’ Perhaps she thought that he had had a deprived childhood, having grown up in what she regarded as a ‘third-world’ country. She did not probe, neither did he enlighten.

It was only because his much-adored older sister had now moved here from her native village thanks to a substantial inheritance that he had to reluctantly revisit his past while on this trip to India. Didi would have been really upset if he had refused to visit her new ‘haveli.’ Her constant harping that he did not visit enough had a grain of truth. He gratefully remembered the times when she had braved the heat, dust, and the occasional camel cart to visit him every fortnight because her village was only a couple of hours away compared to Udaipur. The snacks which she always brought, packed tightly into brass tins had seen him through the nights when the food from the mess where he ate, had refused to make the short journey down his gullet and remained wedged shrapnel-like in his throat. The hiding of these precious treats had now become a habit.

“Yahi address hain na, Sahibji?” the driver’s gravelly voice shook Nandan from the torpor like daze into which he had sunk. He looked up at the sparkling two-story red-brick building with ornate cupolas and a flat roof, typical of this arid part of the world. Didi was already standing at the gate, her face wreathed in smiles. Nandan felt his heart lift. He was back to the time when he waited at the gate of his hostel, his eyes searching for the kind familiarity of her face, especially when he had had a bad week in class or had fared badly in a test.

Despite knowing that he was luckier than most of the others with whom he shared his crowded life, who had journeyed many weary kilometers from all corners of the country and who had to make do with the occasional phone call home he could not shake off the oppressive feeling which came with constantly looking over his shoulder. Everyone here was a competitor, a potential threat to his engineering ambition. And this precluded artless but deep and meaningful friendships. Loneliness lurked amidst the apparent bonhomie. ‘Dog-eat-dog’ world was far too good a term to describe the competition which was the bane of the education system. The odds of landing on the moon were much better than getting his coveted branch of engineering in a desired college for a ‘open category’ candidate like him. The mere thought of a far less meritorious ‘reserved’ candidate overtaking him with no other criterion except a perceived wrong done decades ago made his heart crawl into his throat.

Life had been an endless cycle of swotting, sitting preparatory tests, rushing to the notice board in a hopeful search of finding one’s name in a decent spot in the results, being met with disappointment, handling the sniggers of the toppers and the tirades of the teachers. The rising and setting of the sun and the changing of seasons marked the passage of time, else the world seemed to be at a standstill. Each day like and yet unlike the previous one. Occasionally marred by a holiday, which seemed pointless for the futile hope of rest and recreation it offered. Perhaps Didi noticed him shuddering due to atavistic memory as he stepped out of the car, because she clasped him in a hug for a few seconds longer than usual.

****************************

After dinner, Jijaji turned on the large yet sleek fifty-two-inch wall mounted LED television, which was his pride and joy. Decades of squinting at a small, moody, boxy set which displayed pictures only when it felt like it, had been his chief grouse against village life and the most important deciding factor which marked his move. Even the access to better health-care came a distant second. He was the kind of man who did not even aim for the top of a tree if he could get away with gathering the fruit near the ground.

Local news flashed across the screen in lurid pictures accompanied by bold black type which proclaimed the death of two students by suicide in one of the best coaching institutes in town. Nandan felt himself spiraling into a vortex of darkness like the one he had felt a decade ago. He stumbled his way to the terrace and let the gloaming swallow him into a swirl of dark memories.

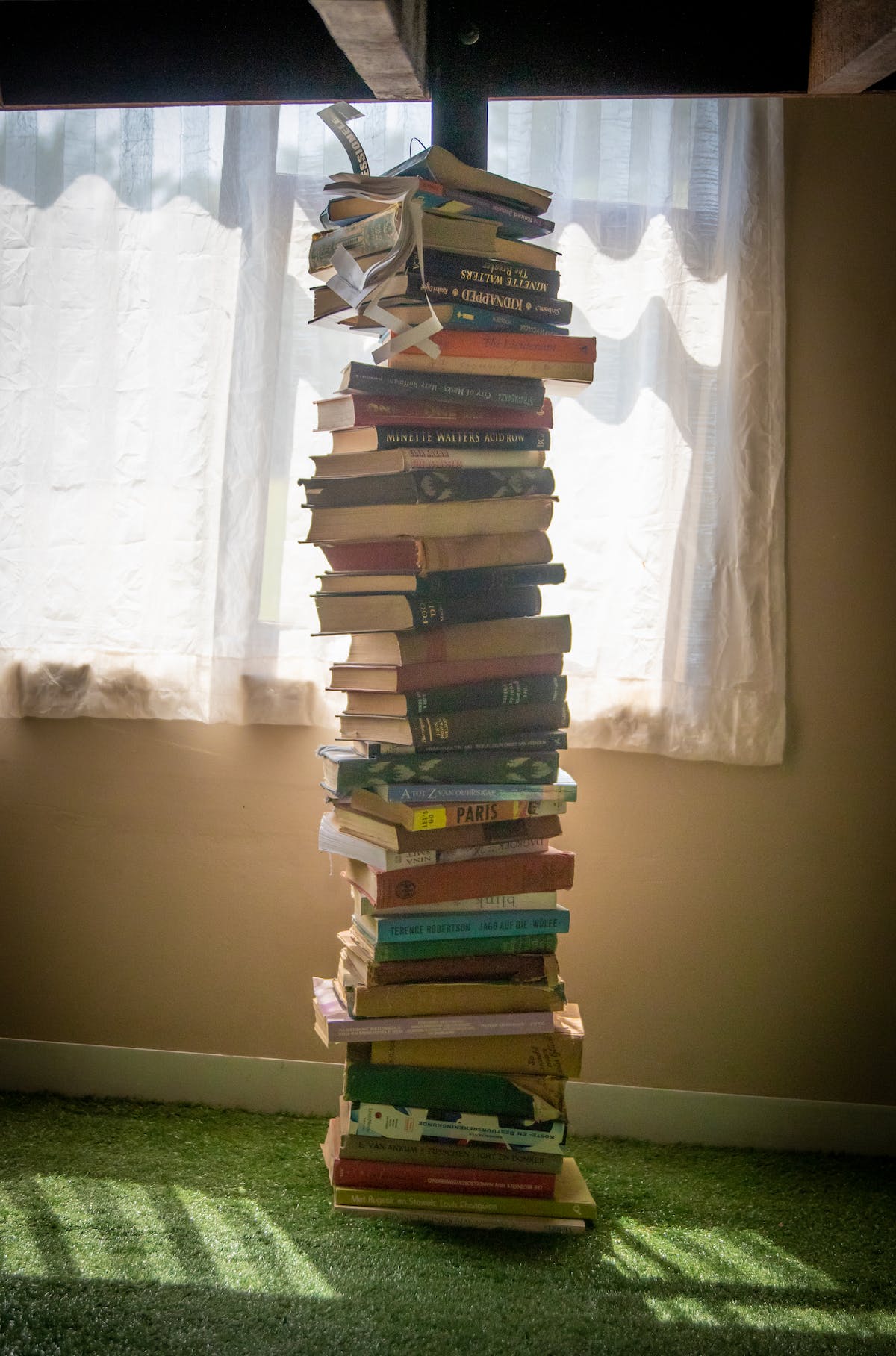

Barely three months remained for the exams. Reams and reams of papers flew all around the rooms. Tables, chairs, and beds creaked and groaned under the weight of teetering piles of fat books, sometimes even giving way when their rickety legs could hold them up no longer. But this was only the inanimate objects. The less said about the animate ones, the students themselves, the better.

One could be excused for thinking that the town was in the grip of a strange kind of palsy. The classes, libraries, hostels, and messes were replete with students who appeared unable to hold their heads up, eyes fixed on the pages of the books on their laps. Just when it seemed possible for the frenzy to grow anymore, a sudden shout went up in the hostel of the largest coaching institute. “The prelims results are out!” In the twinkling of an eye, a crowd had gathered around the notice boards, elbows and knees being used as weapons of distance reduction to help one draw closer to the holy grail to view the outcome of a year and a half of swotting. Nandan peered at the list with hopeful eyes. He had been to hell and back, working through several minor illnesses without a single break.

Today, however was a day of disappointments. While he had never been amongst the top ten in his batch of fifty, he had always been confident of being among the top thirty at least. To his disbelief, he was now ranked forty-fifth. Numbly, he backed out of the crowd. He would not be able to join the special coaching for the top thirty now. Who knew where he would rank in the all-India exams if he could not even make it to the top thirty in a batch of fifty. Suddenly the back-breaking work of the past year and a half seemed pointless and futile. Who was he kidding? Why had he insisted on getting admitted here? He would have been far better off joining a college in Udaipur, getting a Bachelor’s degree, and then joining the family business.

He thought of the anxious calls his parents made every Sunday, enquiring not just about his well-being, but also about his progress. Although his reports were regularly forwarded to them, they did not really grasp the finer nuances of the charts and graphs they entailed. They did not or rather could not know the difference each mark carried in the national rankings. And if they did get an inkling, the worry in their voices compounded his, instead of alleviating it. It was a damning exercise to discuss anything with them.

He reached the room he had called home for some time now. The darkness within reflected the one filling his soul. He threw himself on the bed and allowed the tears to seep from the corners of his tired eyes. What was the point of it all? Even if he did make it, what was the use? More of the grind? More of the same rote? More..more…how much more? “Do you want to continue?” his bitter soul mocked him. “Get ready for the brick-bats and sniggers tomorrow. Ready yourself for being ignored when you take your doubts and queries to the professors. Why will they pay attention to a nobody like you? Everyone will laugh. When you return in ignominy, your parents will have to listen to taunts and jibes too. Why should they put up with a failure like you?” Didi had promised to come today, but perhaps hearing of his failure, she had left. Perhaps she never wanted to meet him. He had brought nothing but trouble, making her journey two hours each way, week upon miserable week. Egged on by an empty stomach and empty heart, he shoved himself upright. The terrace on the eighth floor beckoned, tantalizingly close. Perhaps it was better to end it all. At least there would be an end to this daily misery, this perpetual half-life which he led.

As he stumbled his way out in the dark, his knee caught the table causing something to fall to the floor with a crash and a moment of sanity and curiosity got the better of Nandan, making him turn on his table lamp. A steel tin of toffees lay scattered on the floor, with a scrap of paper wedged into the bottom of the tin. He picked it up and recognised Didi’s scrawling Hindi hand.

“Dear Nandan, I had come some time ago, but you were not in. I must return immediately, but I am leaving some toffees for you. I know that they are your favourites. I had given you a box of them when you failed your terminal exams in class seven and I have never seen you falter since. I am sorry I could not meet you this time, but I will be back in a couple of days and expect my little brother to be standing at the gate. Your Didi.”

The tears in Nandan’s eyes were no more tears of anger, and futility. They were tears of shame for his lack of faith. The moment of madness had passed. Yes, he would work like never before for the next three months and every improved score would be rewarded by one of Didi’s toffees.

As he came back to the present, he thought of the two young lives crushed in the competition. Wiping both the tears of the past and the present, he went to find Didi. He would stay longer. He would visit a couple of coaching classes and find out if he could help in any way to keep the young hopefuls there not just whole in body, but in mind. Exorcising his demons would perhaps help in fighting theirs too.

He would tell everyone the tale of a toffee.

3 replies on “The tale of a toffee”

Absolutely hearttouching…

Yet soooooo subtle.

A lovely tale very much needed in today’s world for all to read. It is deeply moving.

A good read especially with all the depressing news one reads in the morning newspaper.

So important to have that one person to lift your spirits.

Great going Sumedha